Kirātārjunīya is a Sanskrit kavya by Bhāravi, written in the 6th century or earlier. It is an epic poem in eighteen cantos describing the combat between Arjuna and lord Shiva at Indrakeeladri hills in present-day Vijayawadain the guise of a kirāta or mountain-dwelling hunter.

Along with the Naiṣadhacarita and the Shishupala Vadha, it is one of the larger three of the six Sanskrit mahakavyas, or great epics.

It is noted among Sanskrit critics both for its gravity or depth of meaning, and for its forceful and sometimes playful expression. This includes a canto set aside for demonstrating linguistic feats, similar to constrained writing. Later works of epic poetry followed the model of the Kirātārjunīya.

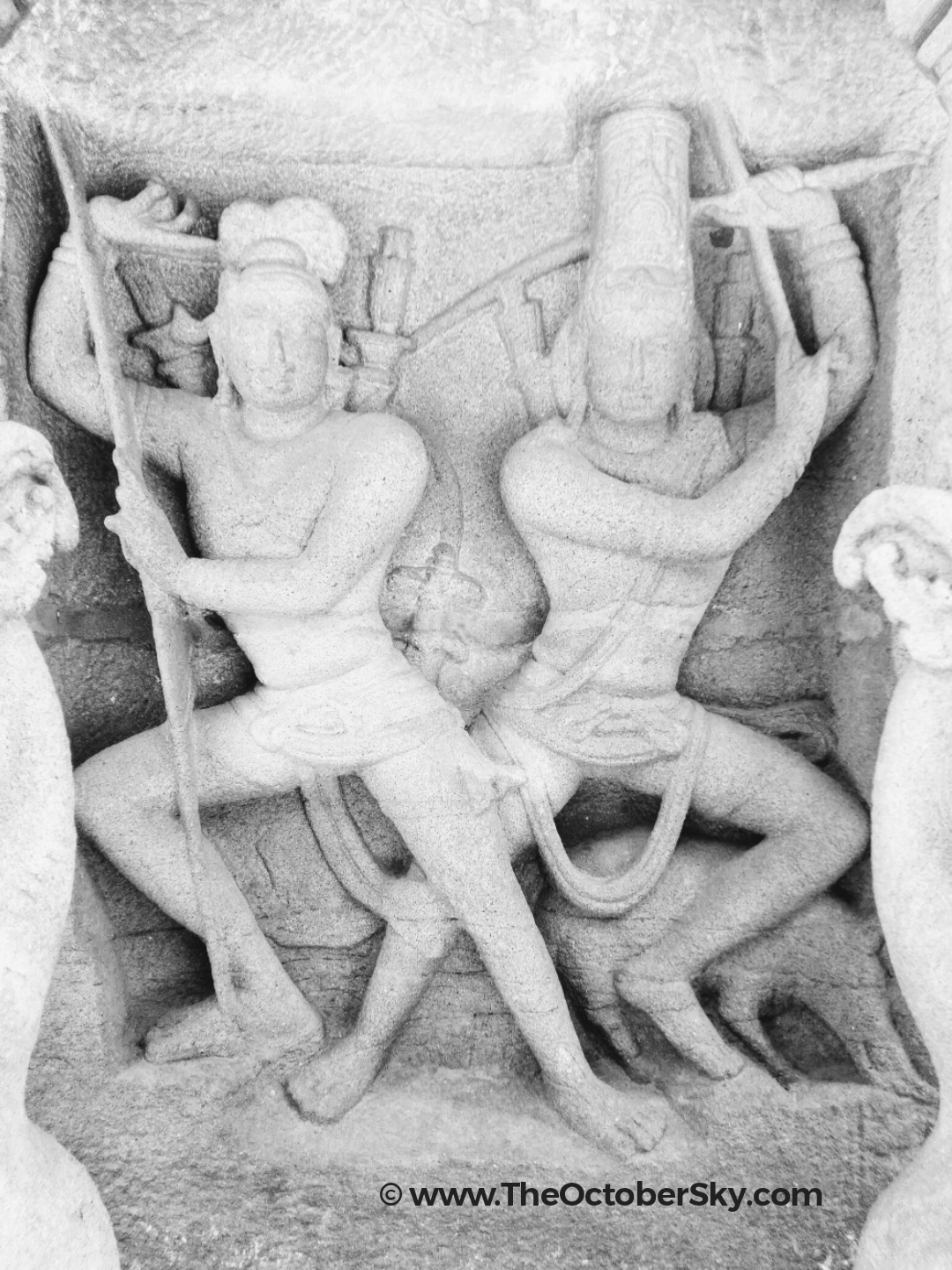

The Kirātārjunīya predominantly features the Vīra rasa, or the mood of valour. It expands upon a minor episode in the Vana Parva(“Forest book”) in the Mahabharata: While the Pandavas are exiled in the forest, Draupadiand Bhima incite Yudhishthira to declare war with the Kauravas, while he does not relent. Finally, Arjuna, at the instruction of Indra, propitiates god Shiva with penance (tapasya) in the forest. Pleased by his austerities, Shiva decides to reward him. When a demon named Muka, the form of a wild boar, charges toward Arjuna, Shiva appears in the form of a Kirāta, a wild mountaineer. Arjuna and the Kirāta simultaneously shoot an arrow at the boar, and kill it. They argue over who shot first, and a battle ensues. They fight for a long time, and Arjuna is shocked that he cannot conquer this Kirāta. Finally, he recognises the god, and surrenders to him. Shiva, pleased with his bravery, gives him the powerful weapon, the Pashupatastra, which later in the Mahabharata aids him against Jayadratha and the Kauravas during the Kurukshetra war.

The following description of the work is from A. K. Warder. Bharavi’s work begins with the word śrī (Fortune), and the last verse of every canto contains the synonym Lakshmi.

In the first canto, a spy of the exiled king Yudhiṣṭhira arrives and informs him of the activities of the Kauravas. Yudhiṣṭhira informs the other Pandavas, and his wife Draupadiattempts to incite him to declare war, upbraiding him for stupidly accepting the exile rather than breaking the agreement and declaring war to regain what is rightfully theirs.

In the second canto, Bhima supports Draupadi, pointing out that it would be shameful to receive their kingdom back as a gift instead of winning it in war, but Yudhiṣṭhira refuses, with a longer speech. Meanwhile, the sage Vyasa arrives.

In the third canto, Vyasa points out that the enemy is stronger, and they must use their time taking actions that would help them win a war, if one were to occur at the end of their exile. He instructs Arjuna to practise ascetism (tapasya) and propitiate Indra to acquire divine weapons for the eventual war. Arjuna departs, after being reminded by Draupadi of the humiliation she has suffered.

In the fifth canto, Arjuna, is led by a Yaksha to the Indrakila mountain, which is described in great detail. Arjuna begins his intense austerities, the severity of which causes disturbance among the gods.

Meanwhile, in the sixth canto, a celestial army of maidens (apsaras) sets out from heaven, in order to eventually distract Arjuna.

The seventh canto describes their passage through the heavens.

In the eighth canto, the nymphs enjoy themselves on the mountain.

The ninth canto describes night, with celebrations of drinking and lovemaking.

In the tenth canto, the nymphs attempt to distract Arjuna, accompanied by musicians and making the best features of all six seasons appear simultaneously. However, they fail, as instead of Arjuna falling in love with them, they fall in love with Arjuna instead.

Finally, in the eleventh canto, Indra arrives as a sage, praises Arjuna’s asceticism, but criticises him for seeking victory and wealth instead of liberation — the goddess of Fortune is fickle and indscriminate. Arjuna stands his ground, explaining his situation and pointing out that conciliation with evil people would lead one into doing wrong actions oneself. He gives a further long speech that forms the heart of the epic, on right conduct, self-respect, resoluteness, dignity, and wisdom. Pleased, Indra reveals himself to his son, and asks him to worship Shiva.

In the twelfth canto, Arjuna begins severe austerities, and, on being implored by the other ascetics, Shiva takes the form of a Kirāta and arrives to meet Arjuna.

In the thirteenth canto, they both shoot the boar. Arjuna goes to retrieve his arrow, and one of the kiratas quarrels with him.

In the remaining five cantos, Arjuna and Shiva fight, Arjuna fails and finally realises whom he is facing, and surrenders to Shiva and wins his benediction.

The Kirātārjunīya is the only known work of Bharavi. It “is regarded to be the most powerful poem in the Sanskrit language”. A. K. Warder considers it the “most perfect epic available to us”, over Aśvaghoṣa’s Buddhacarita, noting its greater force of expression, with more concentration and polish in every detail. Despite using extremely difficult language and rejoicing in the finer points of Sanskrit grammar, Bharavi achieves conciseness and directness. His alliteration, “crisp texture of sound”, and choice of metreclosely correspond to the narrative.

A vyayoga (a kind of play), also named Kirātārjunīya and based on Bharavi’s work, was produced by the Sanskrit dramatist Vatsaraja in the 12th or 13th century.

The authoritative commentary on the Kirātārjunīya, as on the other five mahakayvas, is by Mallinātha (c. 1500 CE). His commentary on the Kirātārjunīya is known as the Ghaṇṭāpatha (the Bell-Road) and explains the multiple layers of compounds and figures of speech present in the verses.

The first Western translation of the poem was by Carl Cappeller into German, published by the Harvard Oriental Series in 1912.There have since been six or more partial translations into English.