“The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.”

Martin Luther King Jr. was the most important voice of the American civil rights movement, which worked for equal rights for all.

He was famous for using nonviolent resistance to overcome injustice, and he never got tired of trying to end segregation laws (laws that prevented blacks from entering certain places, such as restaurants, hotels, and public schools).

He also did all he could to make people realize that “all men are created equal.” Because of his great work, in 1964 King received the Nobel Peace Prize — the youngest person ever to receive this high honor. King was also a Baptist minister.

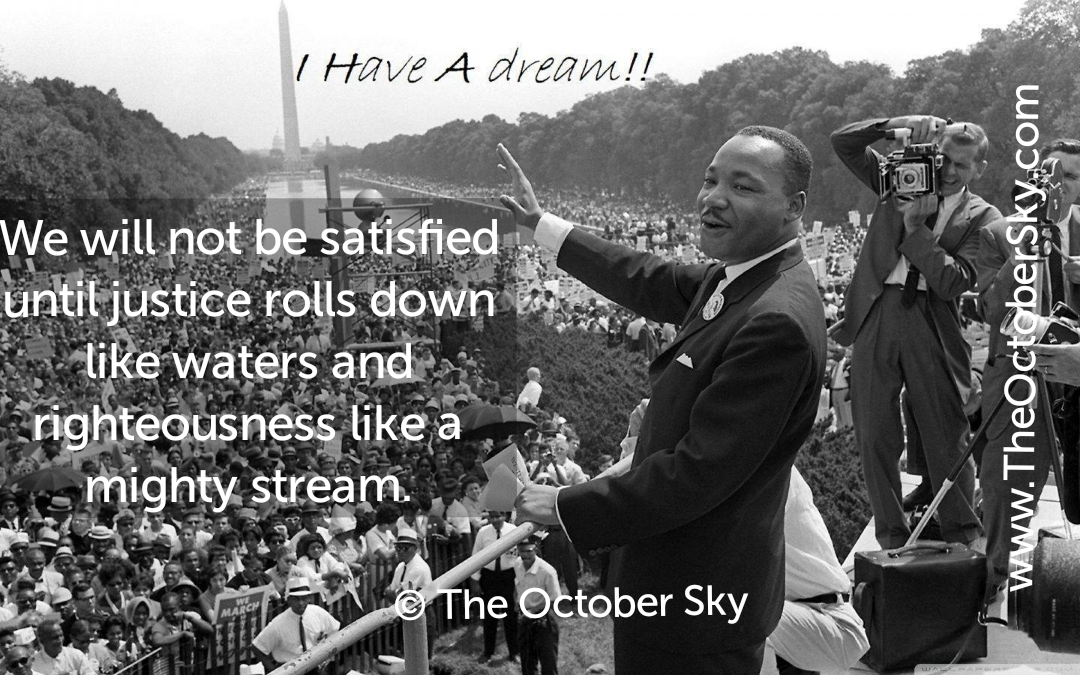

King led the 1955 Montgomery bus boycottand in 1957 became the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference(SCLC). With the SCLC, he led an unsuccessful 1962 struggle against segregation in Albany, Georgia, and helped organize the nonviolent 1963 protests in Birmingham, Alabama. He also helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

On October 14, 1964, King won the Nobel Peace Prize for combating racial inequalitythrough nonviolent resistance. In 1965, he helped organize the Selma to Montgomery marches. The following year, he and the SCLC took the movement north to Chicago to work on segregated housing. In his final years, he expanded his focus to include opposition towards poverty and the Vietnam War. He alienated many of his liberal allies with a 1967 speech titled “Beyond Vietnam”. J. Edgar

Hoover considered him a radical and made him an object of the FBI’s COINTELPRO from 1963 on. FBI agents investigated him for possible communist ties, recorded his extramarital liaisons and reported on them to government officials, and on one occasion mailed King a threatening anonymous letter, which he interpreted as an attempt to make him commit suicide.

In 1968, King was planning a national occupation of Washington, D.C., to be called the Poor People’s Campaign, when he was assassinated on April 4 in Memphis, Tennessee. His death was followed by riots in many U.S. cities. Allegations that James Earl Ray, the man convicted and imprisoned of killing King, had been framed or acted in concert with government agents persisted for decades after the shooting. Sentenced to 99 years in prison for King’s murder, effectively a life sentence as Ray was 41 at the time of conviction, Ray served 29 years of his sentence and died from hepatitis in 1998 while in prison.

King was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal. Martin Luther King Jr. Day was established as a holiday in numerous cities and states beginning in 1971; the holiday was enacted at the federal level by legislation signed by President Ronald Reaganin 1986. Hundreds of streets in the U.S. have been renamed in his honor, and a county in Washington State was also rededicated for him. The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., was dedicated in 2011.

“I have a Dream”

The “I Have a Dream” speech by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was delivered during the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. He gave the speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.; this speech expresses King’s notorious hope for America and the need for change. He opens the speech by stating how happy he is to be with the marchers, and emphasizes the historical significance of their march by calling it “the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.”

He talks about Abraham Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation one hundred years before the march. He calls that proclamation “a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity,” where “their” refers to those who were enslaved. King then comes to the problems faced by African Americans in 1963, saying that one hundred years later, they still are not free. Instead, they are “sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.” He also discusses the poverty endured by black Americans. King talks about when the founders of the nation (“the architects of our republic”) wrote the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

He says they were writing a promissory note to every American, that all men were guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, and that this included black men as well as white. He states that America defaulted on that check where black citizens are concerned by denying them those rights. “America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds,” he says.

King then adopts a more hopeful tone by adding that the “bank of justice” is not bankrupt. He also states that there is urgency in their cause: “This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.” He uses the seasons as a metaphor to describe this urgency by saying that the legitimate discontent of African Americans is a “sweltering summer,” and that freedom and equality will be an “invigorating autumn.” He also promises that this protest is not going away. It’s not about voicing grievances and then going back to the status quo: “The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges,” he states. King then cautions his people not to commit any wrongful deeds. He says, “Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.” This is a crucially important sentiment, as King’s leadership was defined by civil disobedience, not violence. He proved that real legal change could be made without resorting to violence. Though there was much violence during the Civil Rights movement, he was always for peace, and urged others to protest peacefully, what he calls in his speech “the high plane of dignity and discipline.” He also stresses the importance of recognizing white people who want to protest for this same cause—those allies that are necessary to its success. King provides some specific goals. He says they can’t stop marching so long as they suffer police brutality, so long as they’re turned away from hotels, so long as they’re confined to ghettos, so long as they’re subject to segregation, and so long as they do not have the right to vote. He then recognizes the struggles that many of the marchers have already endured, and asks them to undertake that struggle again, and to have hope that their situation can and will change.

Then comes the most famous part of this speech, for which it is titled. King says his dream is “deeply rooted in the American dream.” This reinforces the protestors’ rights to equality in America. He says he dreams that “the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.” This emphasizes the need for black and white Americans to work together.

Central to the message of this speech, and the Civil Rights movement more generally, is this line: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” He talks about the importance of faith, and that “all flesh shall see [the glory of the Lord] together.” That faith, he says, will help them in the struggles they’ve faced, the struggles they still face, and those struggles yet to come as they peacefully fight for liberty and equality. King then uses a line from the song, “My Country ‘Tis of Thee”: “This will be the day, this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning: ‘My country, ‘tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim’s pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring!’” Only by realizing this as truth, King says, can America become a great nation.

He begins the next section by mentioning mountainsides throughout the country, repeating “Let freedom ring.” King closes the speech with another iconic line: “When all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing the words of the old Negro spiritual: ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!’”

He was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, when he was just 39 years old. His birthday is now observed as a national holiday on the third Monday in January.