Archaeologists from Germany and Kurdistan have discovered a 3400-year-old Mittani Empire-era city on the Tigris River. Early this year, the community arose from the waters of the Mosul reservoir as water levels dropped rapidly owing to Iraq’s severe drought. The enormous city with a palace and other massive buildings could be ancient Zakhiku, which is said to have been a major Mittani centre (ca. 1550-1350 BC).

Iraq is one of the countries most affected by climate change in the globe. For months, the south of the country, in particular, has been suffering from severe drought. Since December, enormous amounts of water have been pulled down from the Mosul reservoir, Iraq’s most major water storage, to keep crops from drying up. This led to the reappearance of a Bronze Age city that had been submerged decades ago without any prior archaeological investigations. It is located in the Iraqi Kurdistan Region of Kemune.

Archaeologists were now under pressure to excavate and document at least parts of this vast, important metropolis before it was resubmerged as a result of this unforeseen disaster. Dr. Hasan Ahmed Qasim, chairman of the Kurdistan Archaeology Organization, and Jun.-Prof. Dr. Ivana Puljiz, University of Freiburg, and Prof. Dr. Peter Pfälzner, University of Tübingen, spontaneously decided to conduct cooperative rescue excavations at Kemune. In partnership with the Directorate of Antiquities and Heritage in Duhok, these took place in January and February 2022. (Kurdistan Region of Iraq).

Within days, a team for the rescue excavations had been assembled. The Fritz Thyssen Foundation, through the University of Freiburg, provided funding for the project on short notice. Because it was unclear when the reservoir’s water level would rise again, the German-Kurdish archaeological team was under extreme time constraints.

The researchers were able to map the metropolis in a relatively short period of time. A gigantic fortification with wall and towers, a monumental, multi-story storage building, and an industrial complex were discovered in addition to a palace, which had already been documented during a brief campaign in 2018. The sprawling urban complex dates from the Mittani Empire (about 1550-1350 BC), which ruled over most of northern Mesopotamia and Syria.

“The huge magazine building is of particular importance because enormous quantities of goods must have been stored in it, probably brought from all over the region,” says Puljiz. Qasim concludes, “The excavation results show that the site was an important center in the Mittani Empire.”

Despite the fact that the walls are composed of sun-dried mud bricks and have been under water for more than 40 years, the research team was astounded by how well maintained they were — sometimes to a height of several metres. The city was devastated in an earthquake in 1350 BC, during which the collapsing upper parts of the walls concealed the buildings, resulting in their good preservation.

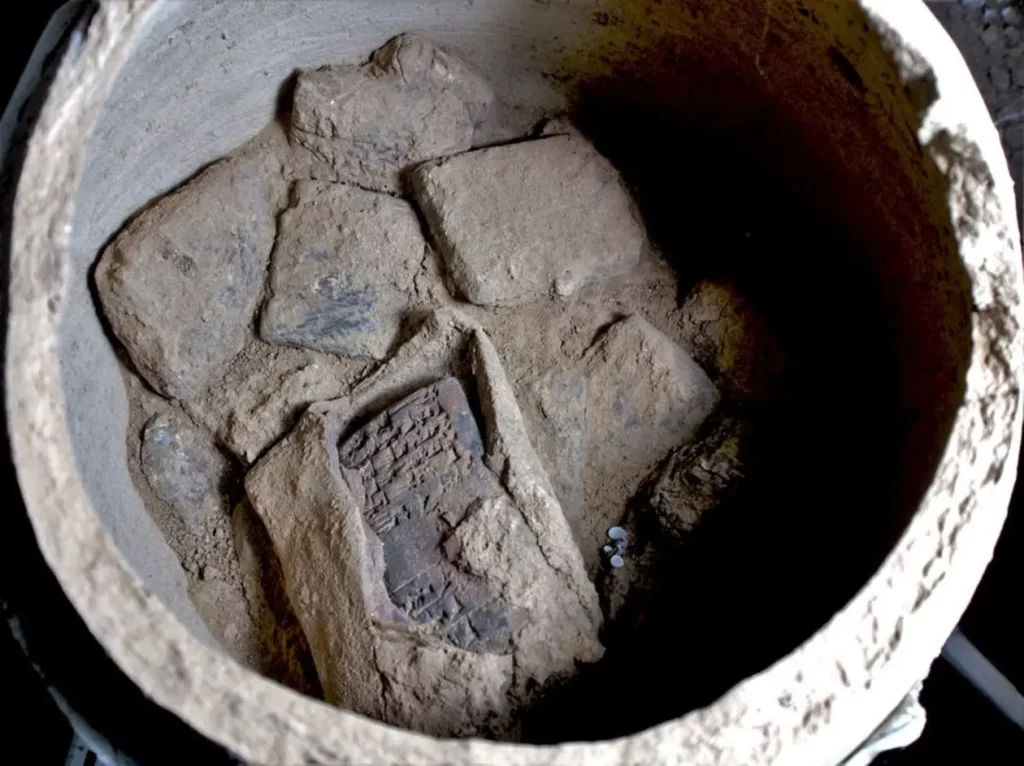

The finding of five ceramic containers containing an archive of over 100 cuneiform tablets is very interesting. They date from the Middle Assyrian period, shortly after the city was devastated by an earthquake. Some clay tablets, which could be letters, are still sealed inside their clay envelopes. The researchers expect that this find may reveal significant details concerning the end of Mittani authority and the beginning of Assyrian rule in the area. “It is close to a miracle that cuneiform tablets made of unfired clay survived so many decades under water,” Pfälzner adds.

As part of an intensive conservation project supported by the Gerda Henkel Foundation, the excavated buildings were totally covered with tight-fitting plastic sheeting and topped with gravel fill to prevent additional harm to the historic site from rising water. During floods, this is done to protect the unbaked clay walls and any other treasures still buried in the ruins. The site is now entirely submerged once more.