It’s no secret that the Louvre has one of the world’s most stunning collections of art.

In addition to the Mona Lisa and an entire Michelangelo Gallery, the major museum also excels in antiquities, with gems that include a Great Sphinx, the Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace.

Winged Victory of Samothrace

Though this marble masterpieceremains one of history’s most famous sculptures, many people may not be aware of its history—including its ancient roots, 19th-century discovery, and soaring influence on modern and contemporary art.

Origin and History

The exact origins of the Winged Victory of Samothrace are not known. However, archaeologists and art historians have extensively studied the sculpture in order to estimate its age, intention, and subject matter.

According to the Louvre, the piece was likely crafted by the people of Rhodes, a Greek island, in the early second century BCE. This places its creation at the heart of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE-31 CE). This ancient art movement is particularly renowned for its expressive sculptures of mythological subjects in motion—an approach embodied by the Winged Victory.

The 18-foot sculpture depicts Nike, the Greek goddess of victory. As wet and wind-blown drapery clings to her body, the winged figure triumphantly steps toward the front of a ship, leading historians to conclude that it was created to commemorate a successful sea battle.

The statue was one of many marble pieces that adorned the Sanctuary of the Great Gods, an ancient temple complex on the island of Samothrace. This seaside shrine was dedicated to the Mystery religion, or secret cult, of the Great Mother.

Given both the prevalence of naval battles during this time and its close proximity to the Aegean’s widely-used maritime routes, the shrine featured several sea-inspired monuments. These included dedicated columns, important ships, and, of course, the Winged Victory, which was placed in a rock niche (possibly a grotto) that overlooked the shrine’s theatre.

Discovery of the Sculpture

French diplomat and amateur archaeologist Charles Champoiseauunearthed the Winged Victory in April of 1863. While he reassembled 23 blocks that compose the ship, he sent the figure back to Paris just as he found it: in three pieces.

The base, torso, legs, and left wing eventually reached the Louvre, where they were reassembled in the Carytid Room of classical antiquities. The museum also added a plaster wing to the sculpture—an addition that remains today—but did not opt to recreate the head or arms.

However, nearly 90 years after Champoiseau discovered the fragmented figure, archaeologists from Austria uncovered missing pieces, including Nike’s right hand. Unfortunately, the hand had no way of being reattached to the sculpture, as the figure remained armless. Still, its unearthing was extremely important, as the unclasped hand disproved an early theory that the figure had originally been grasping an object.

“It has been suggested that the Victory held a trumpet, a wreath, or a fillet in her right hand,” The Louvre explains. “However, the hand found in Samothrace in 1950 had an open palm and two outstretched fingers, suggesting that she was not holding anything and was simply holding her hand up in a gesture of greeting.”

Today, the fragmented hand can be viewed at the top of the Louvre’s Daru Staircase, where the Winged Victory has been on display since 1883.

Hellenistic Realism

Like other Hellenistic sculptures, the Winged Victory is admired for its naturalistic anatomy and, consequently, its realistic depiction of movement.

To suggest a body in motion, the artist positioned Nike in an asymmetrical stance. Known as contrapposto(“counterpose”), this pose implies movement through the use of realistic weight distribution and an S-shaped body.

Other famous sculptures that demonstrate this classical approach to conveying the human body are The Walking Man by Rodin and Michelangelo’s David.

Another element that helps suggest movement is the billowing fabric draped across the figure’s body. As Nike dramatically steps forward, the seemingly translucent garment twists around her waist and wraps around her legs.

According to the Louvre, this “highly theatrical presentation—combined with the goddess’s monumentality, wide wingspan, and the vigor of her forward-thrusting body—reinforces the reality of the scene”

Legacy

Today, the Winged Victory of Samothrace remains one of the most celebrated sculptures on earth. Since making its debut at the Louvre in the 19th century, it has inspired countless artists. Surrealist Salvador Dalí directly appropriated this sculpture for his Double Nike de Samothrace (1973), and Futurist Umberto Boccioni employed the figure’s iconic stance for his Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913).

While these modern interpretations undoubtedly capture the spirit of the piece, no other Winged Victory can captivate audiences as triumphantly as the original treasure

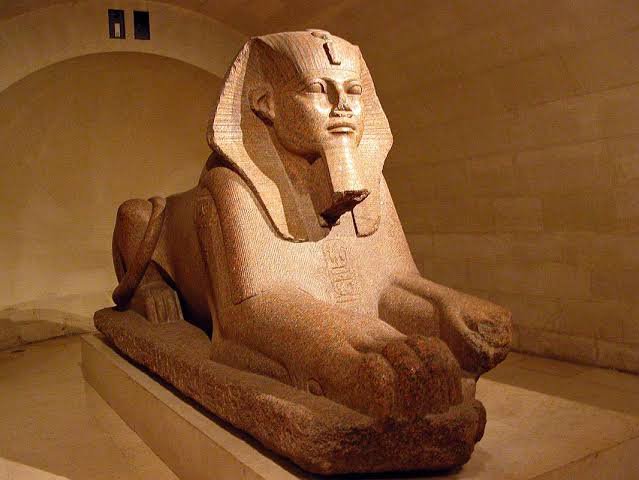

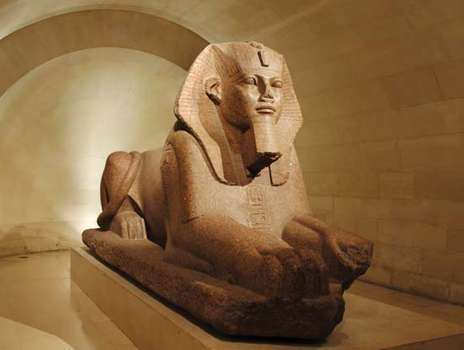

Great Sphinx of Tanis

The sphinx is a fabulous creature with the body of a lion and the head of a king. This one was successively inscribed with the names of the pharaohs Ammenemes II (12th Dynasty, 1929-1895 BC), Merneptah (19th Dynasty, 1212-02 BC) and Shoshenq I (22nd Dynasty, 945-24 BC). According to archaeologists, certain details suggest that this sphinx dates to an earlier period – the Old Kingdom (c. 2600 BC).

Tanis

This is one of the largest sphinxes outside of Egypt. It was found in 1825 among the ruins of the Temple of Amun at Tanis (the capital of Egypt during the 21st and 22nd dynasties). This impressive stone sculpture with its precise details and polished surfaces is a work of admirable craftsmanship. The recumbent lion, with tense body and outstretched claws, gives the impression of being ready to leap. The shen hieroglyph sculpted on the plinth under each paw evokes a cartouche, confirming the royal nature of the monument.

Modifications

The legible inscriptions are all “usurpations”, i.e. traces of subsequent modifications to the monument. The names of Merneptah (19th Dynasty) and Sheshonq (22nd Dynasty) are legible. The original texts (traces of which are still visible in places) were deliberately erased and replaced. It is therefore impossible to date this statue with certainty, especially as the face does not resemble any known, well-documented royal portrait. In view of this uncertainty, Egyptologists are divided: some date the sphinx to the 12th Dynasty, others to the 6th or even the 4th.

Shesep-ankh

The Greek word “sphinx”, commonly used to refer to the Egyptian statues representing a lion with a human head, was not the original term. The appropriate Egyptian appellation for a statue or image of this kind was shesep-ankh (“living image”). The creature was a symbolic representation of the close relationship between the sun god (the lion’s body) and the king (the human head), and was the “living image of the king”, demonstrating his strength and his close association with Ra.

The sphinx was always positioned either as (recumbent) guardian and protector of places where gods appeared – such as the horizon, and temple entrances – or as (upright) defender of Egypt against hostile forces, whom he trampled underfoot.

Bibliography

Christiane Ziegler, Les Statues égyptiennes de l’Ancien Empire, 1997, Réunion des musées nationaux p. 39

G. Andreu, M.-H Ruthscowskaya, L’Egypte ancienne au Louvre, 1997, Hachette, pp. 52 à 54

Nadine Cherpion, “En reconsidérant le grand sphinx du Louvre (A 23)”, in Revue d’égyptologie, 1991, t. 42, pp. 25 à 41

Jean Leclant, Le Temps des pyramides, 1978, Gallimard, coll. “L’univers des formes”, t. 1, p. 213

Jacques Vandier, Manuel d’archéologie égyptienne, 1958, Picard, t. 3, p. 56

Information Via Louvre Museum

Venus De Milo

As one of art history’s most significant sculptures, the Venus de Milo continues to captivate audiences today. Located in the Louvre Museum, the marble masterpiece is celebrated for its Hellenistic artistry, renowned for its beauty, and famous for its absent arms.

Like many other treasured antiquities, the story behind the statue was entirely unknown when it was unearthed in the 19th century. Today, however, archaeologists and art historians have managed to piece together a narrative that explores and explains its possible provenance—though the sculpted goddess remains shrouded in mystery.

What is the Venus de Milo?

Known also as the Aphrodite of Milos, the Venus de Milo is a marble sculpture that was likely created by Alexandros of Antioch during the late 2nd century BC. It features a nearly nude, larger-than-life (6 feet, 8 inches tall) female figure posed in a classical S-curve.

Her body is composed of two blocks of marble as well as “several parts [that] were sculpted separately (bust, legs, left arm and foot),” according to the Louvre. Furthermore, the sculpture was likely colorfully painted and adorned with jewelry, though no pigment or metal remain on the marble today.

Due to her nudity and the sinuous shape of her body, the figure is widely believed to be Venus, the goddess of love. However, she may also represent Amphitrite—the goddess of the sea—who held special significance on the island where the work of art was found.

VENUS (APHRODITE)

Leave a Reply