This post is all about the Gouache paintings sketched at Tanjore, Southern part of India around 18-19 centuries, that are on display at British Museum

Gouache – opaque watercolor, or Gouache, is one type of watermedia, paint consisting of natural pigment, water, a binding agent (usually gum arabic or dextrin, and sometimes additional inert material. Gouache is designed to be used with opaque methods of painting. It is used most consistently by commercial artists for posters, illustrations, comics, and for other design work.

Gouache has a considerable history going back over 600 years. It is similar to watercolor in that it can be re-wetted, it dries to a matte finish, and the paint can become infused with its paper support. It is similar to acrylic or oil paints in that it is normally used in an opaque painting style and it can form a superficial layer. Many manufacturers of watercolor paints also produce gouache and the two can easily be used together.

Gouache paint is similar to watercolor, however modified to make it opaque. Just as in watercolor, the binding agent has traditionally been gum arabic but since the late nineteenth century cheaper varieties use yellow dextrin. When the paint is sold as a paste, e.g. in tubes, the dextrin has usually been mixed with an equal volume of water. To improve the adhesive and hygroscopic qualities of the paint, as well as the flexibility of the rather brittle paint layer after drying, propylene glycol is often added.

Gouache differs from watercolor in that the particles are typically larger, the ratio of pigment to binder is much higher, and an additional white filler such as chalk, a “body”, may be part of the paint. This makes gouache heavier and more opaque, with greater reflective qualities.

Gouache generally dries to a different value than it appears when wet (lighter tones generally dry darker and darker tones tend to dry lighter), which can make it difficult to match colors over multiple painting sessions. Its quick coverage and total hiding power mean that gouache lends itself to more direct painting techniques than watercolor. “En plein air” paintings take advantage of this, as do the works of J. M. W. Turner.

Gouache is used most consistently by commercial artists for works such as posters, illustrations, comics, and for other design work. Most 20th-century animations used it to create an opaque color on a cel with watercolor paint used for the backgrounds. Using gouache as “poster paint” is desirable for its speed as the paint layer dries completely by the relatively quick evaporation of the water.

The use of gouache is not restricted to the basic opaque painting techniques using a brush and watercolor paper. It is often applied with an airbrush. As with all types of paint, gouache has been used on unusual surfaces from Braille paper to cardboard.

A variation of traditional application is the method used in the gouaches découpées (cut collages) created by Henri Matisse. His Blue Nudes series is a good example of the technique. A new variation in the formula of the paint is acrylic gouache.

The term, derived from the Italian guazzo, also refers to paintings using this opaque method. “Guazzo”, Italian for “mud”, was originally a term applied to the early 16th century practice of applying oil paint over a tempera base, which could give a matted effect. In the 18th century in France, the term gouache was applied to opaque watermedia, although the technique is considerably older; it was employed as early as the 9th century in Persian miniature and had by the 14th century spread to Europe.

During the eighteenth century gouache was often used in a mixed technique, for adding fine details in pastel paintings. Gouache was typically made by mixing water colours based on gum arabic with an opaque white pigment. In the nineteenth century, water colours began to be industrially produced in tubes and a “Chinese white” tube was added to boxes for this purpose. Later that century, for decorative uses “poster paint” was mass-produced, based on the much cheaper dextrin binder. It was sold in cans or as a powder to be mixed with water. The dextrin replaced older paint types based on hide glue or size. During the twentieth century, gouache began to be specially manufactured in tubes for more refined artistic purposes. Initially, gum arabic was used as a binder but soon cheaper brands were based on dextrin, as is most paint for children.

Posting some Miniature Gauche Paintings, that are on display at British Museum.

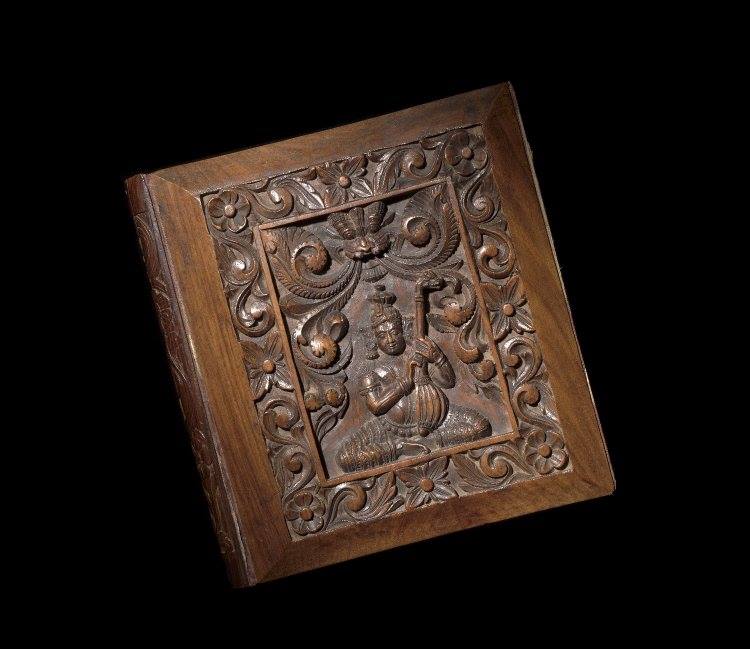

Some of these are encased within a Wooden Box. Almost all these paintings were made in Tanjore, India ( under Maratha Influence ) during the Mid 18th Century to early 19th Century by the Artists with their captions on them and with Telugu Captions by local Artists.

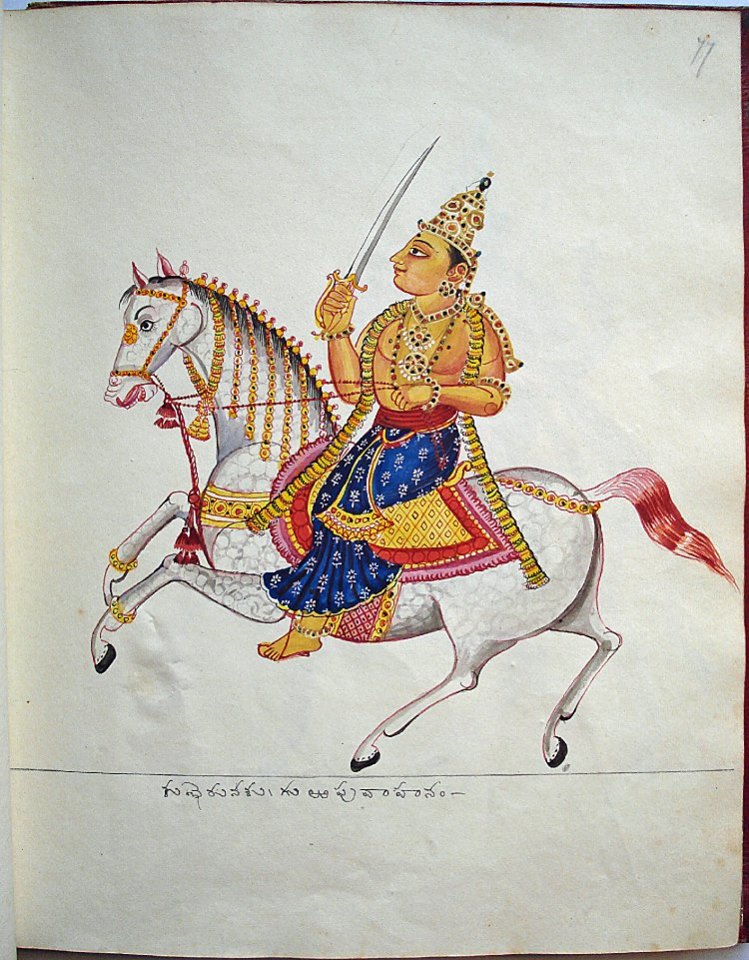

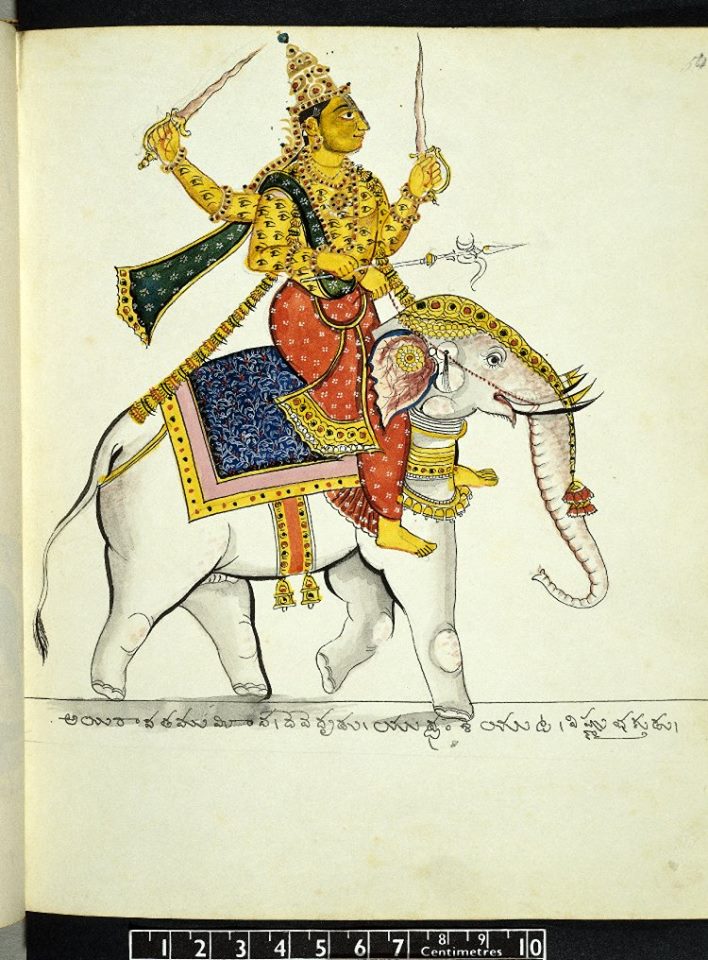

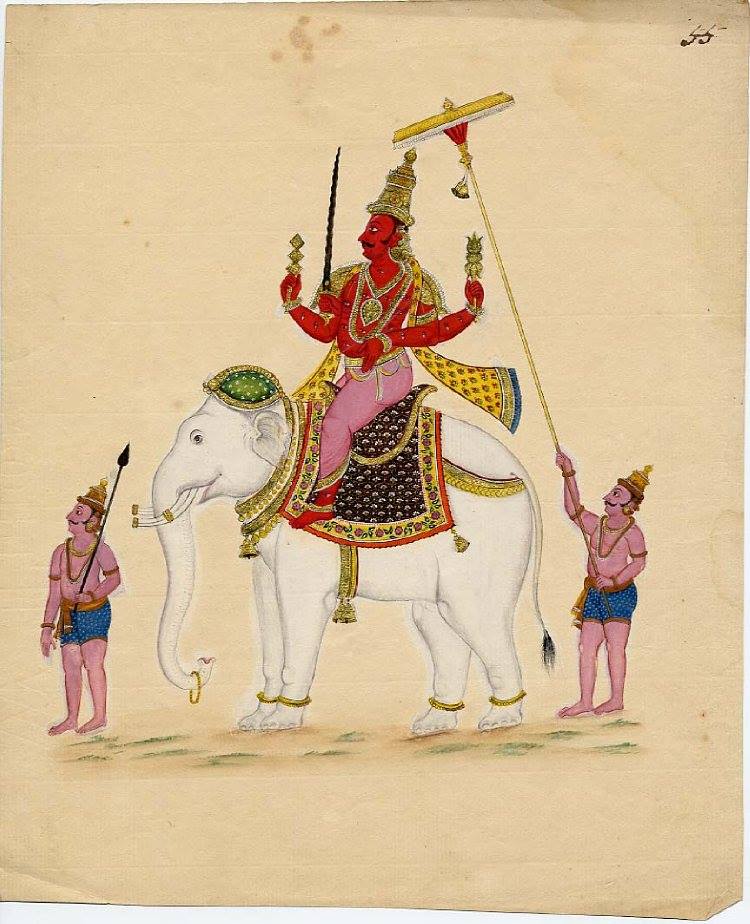

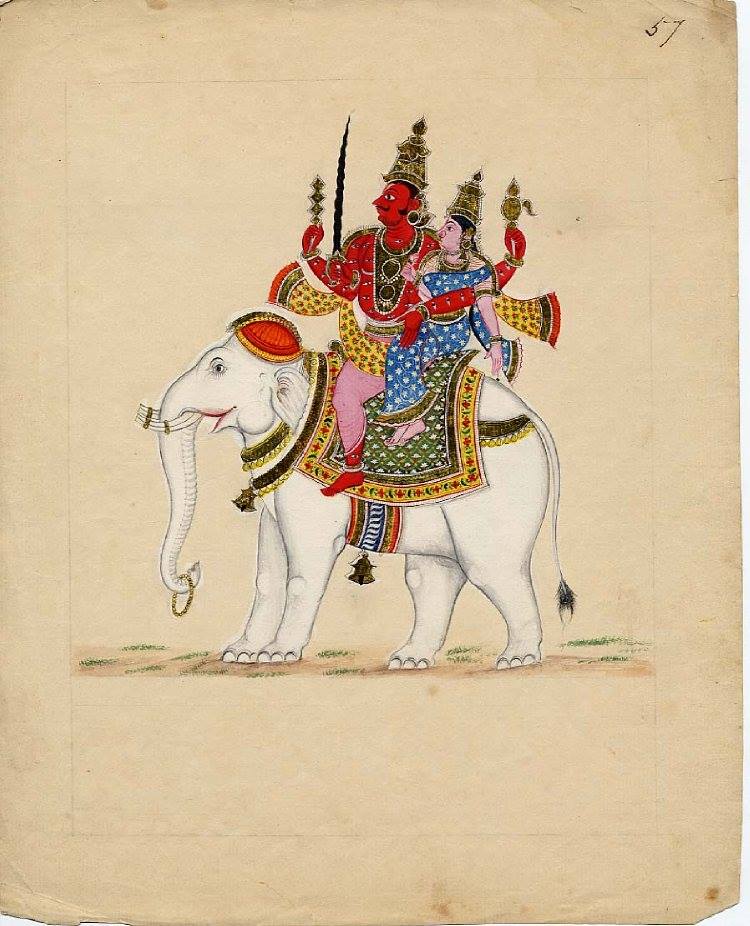

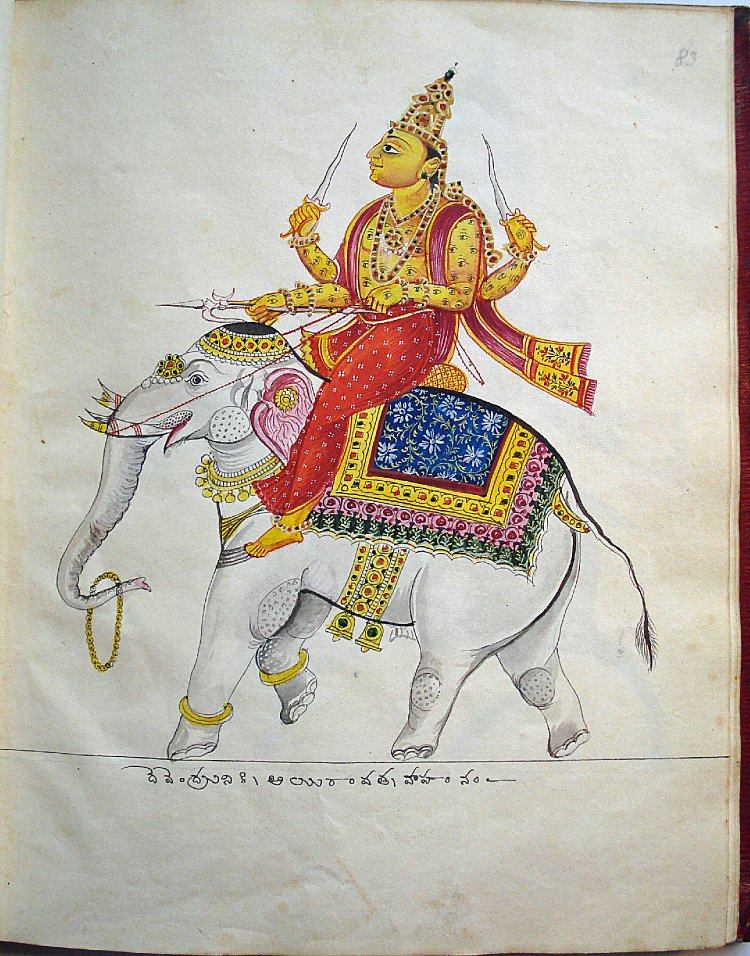

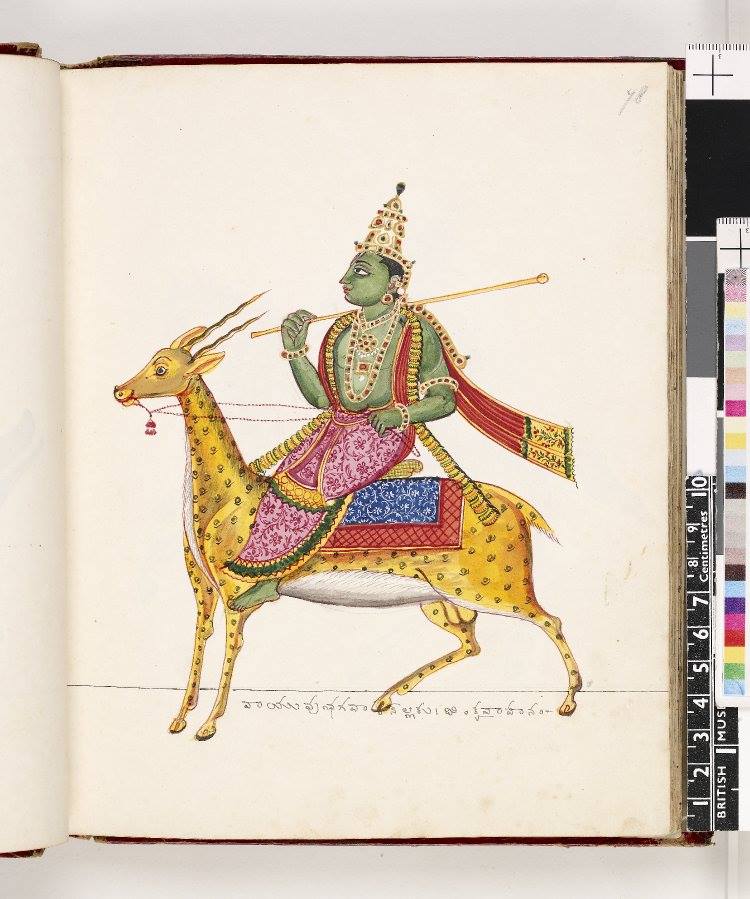

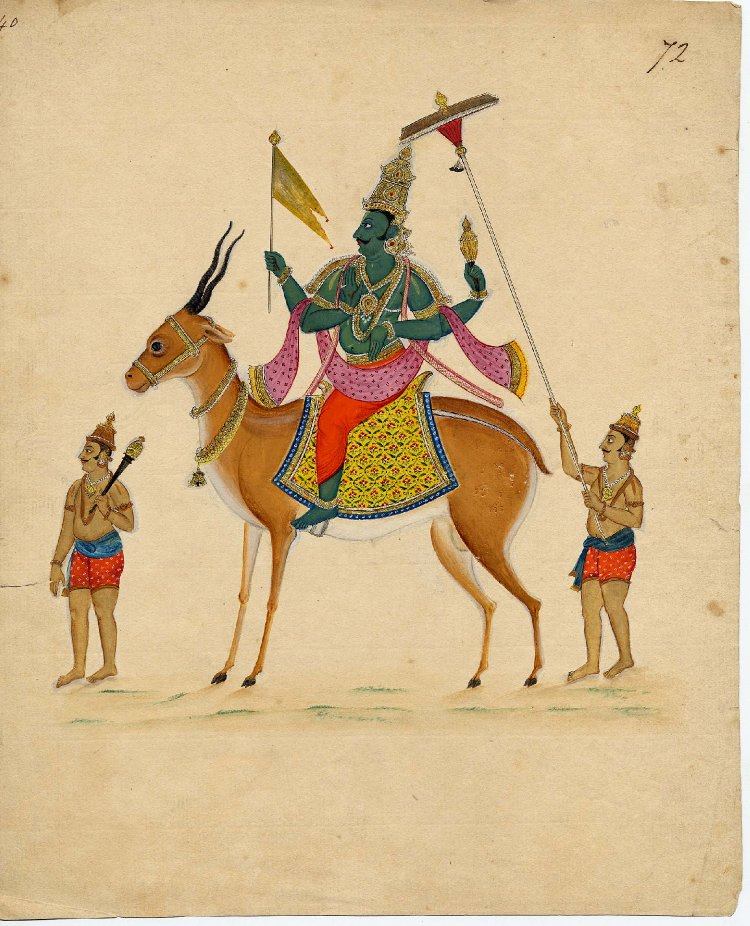

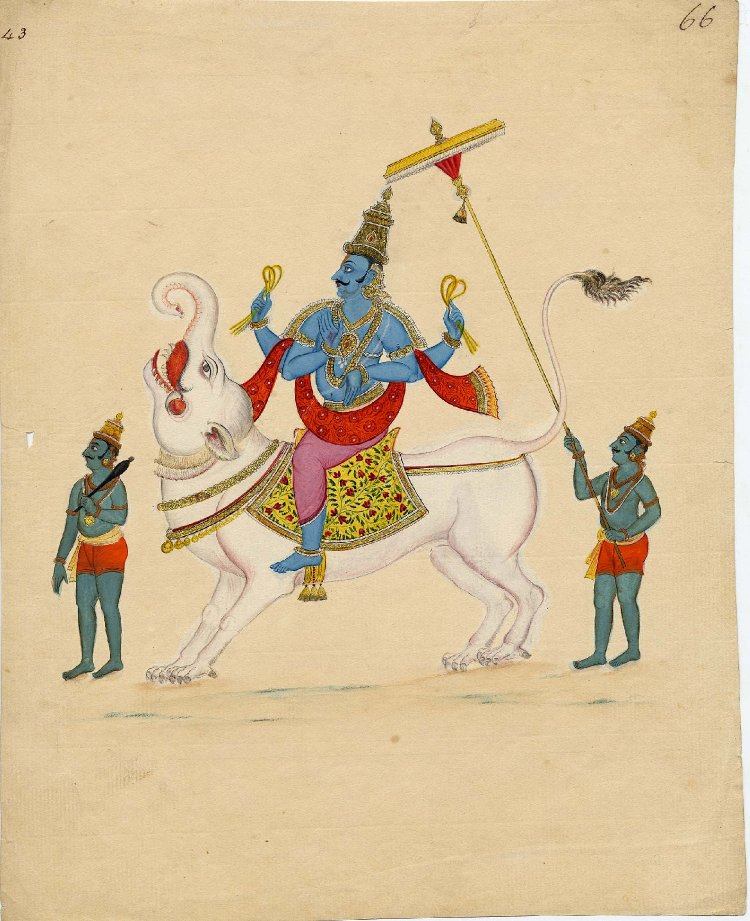

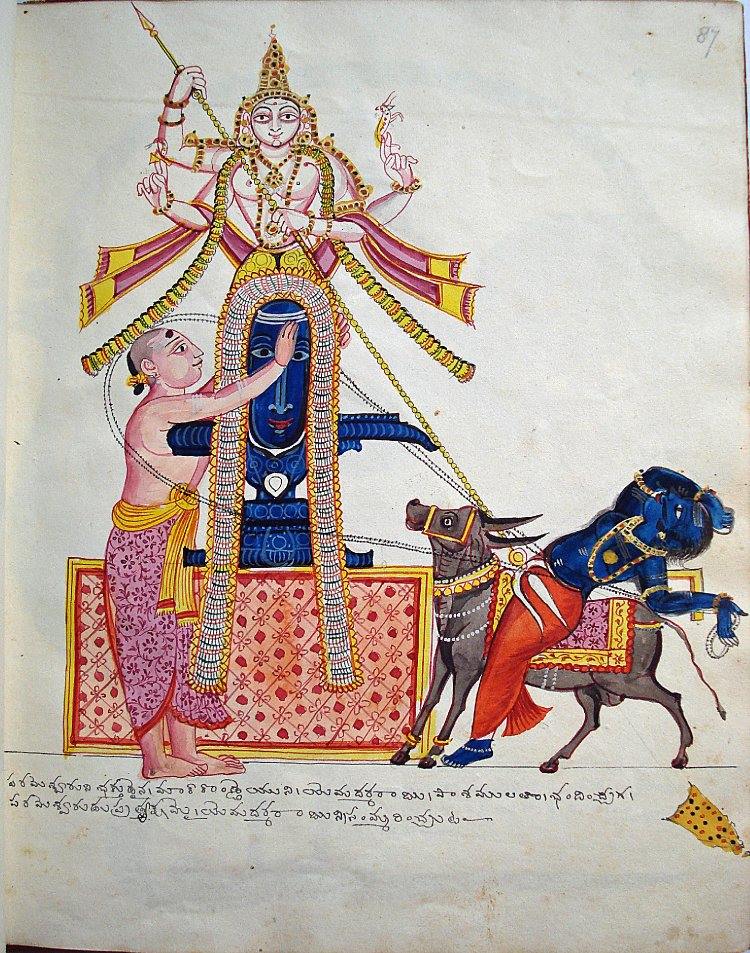

Here posting the set on Ashtadikapalaka or Guardians of Eight Cardinal Directions.

The Guardians of the Directions are the deities who rule the specific directions of space according to Hinduism and Vajrayāna Buddhism—especially Kālacakra. As a group of eight deities, they are called Aṣṭa-Dikpāla, literally meaning guardians of eight directions. They are often augmented with two extra deities for the ten directions (the two extra directions being zenith and nadir), when they are known as the Daśa-Dikpāla. In Hinduism it is traditional to represent their images on the walls and ceilings of Hindu temples. They are also often portrayed in Jain temples. Ancient Java and Bali Hinduism recognize Nava-Dikpāla, literally meaning guardians of nine directions, that consist of eight directions with one addition in the center. The nine guardian gods of directions is called Dewata Nawa Sanga (Nine guardian devata). The diagram of these guardian gods of directions is featured in Surya Majapahit, the emblem of Majapahit empire.

From British Museum, Wooden Box with Goddess Saraswati on its lid, containing Miniature Gauche Water Colour Paintings

Esanan rides the Bull, guards the Northeast direction, holding the Trishula with Sati as his consort.

Kubera, God of the Riches, Guardian for the North Direction, atop his Horse, wielding the Gada or Sword. His consort is Bhadra.

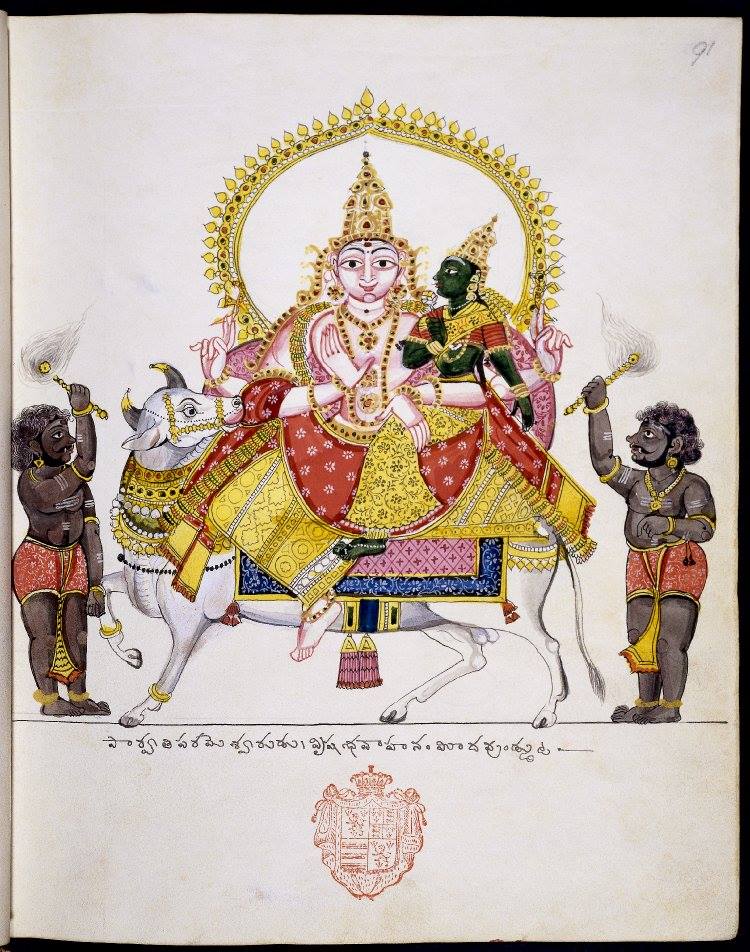

Indra Guards the east Cardinal Direction, rules from Amaravathy with all the Suras, rides the white Elephant, Airavatha that emerged during Samudra Mandhan and holds the Vajra as his weapon. His consort is Sachi or Indrani. Here he is shown with the thousand eyes that he incurred as a wrath from Gautama Maharishi.

Vayu guards the Northwest direction, rides the spotted Gazelle, and holds the Staff or Flag in his hands. Svasti is his consort. His Kingdom is the Pawanloka.

Varuna, God of the sea or Oceans, Guardian of the West Direction, rides the makara Vahana, holding the Pasa or Nagapasa in his hands. His consort is Varuni.

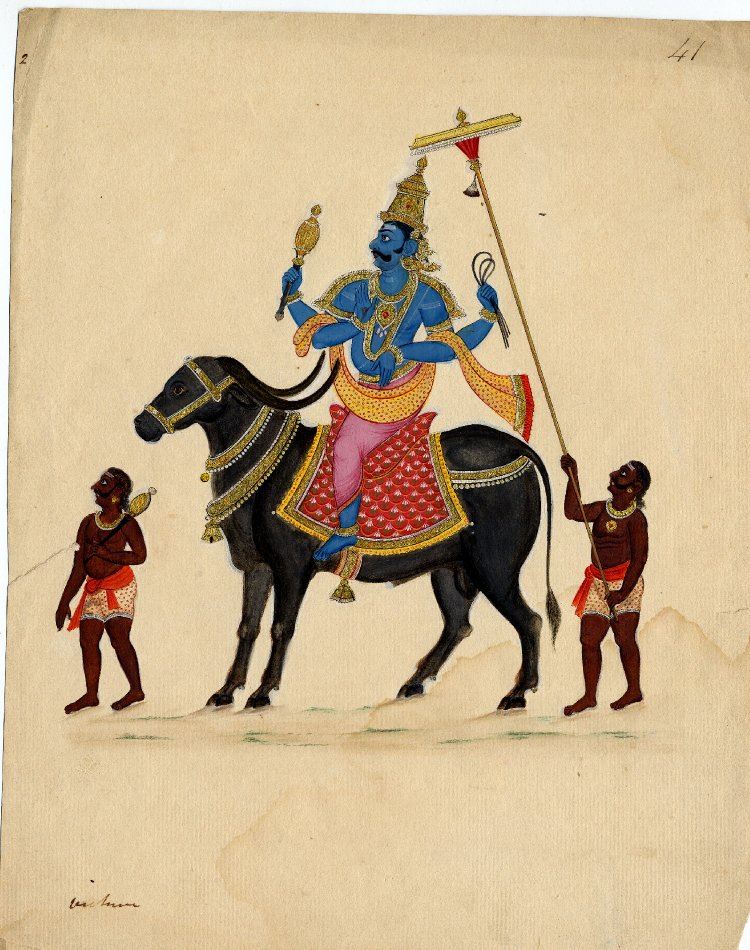

Yama, Lord of Death, Guardian of the South Direction, rides the Black ( Water ) Buffalo, armed with his Danda and Noose, born of Surya with sandhya, and lives in Naraka or Yamaloka, is also considered to be the God of Justice or Dharma.

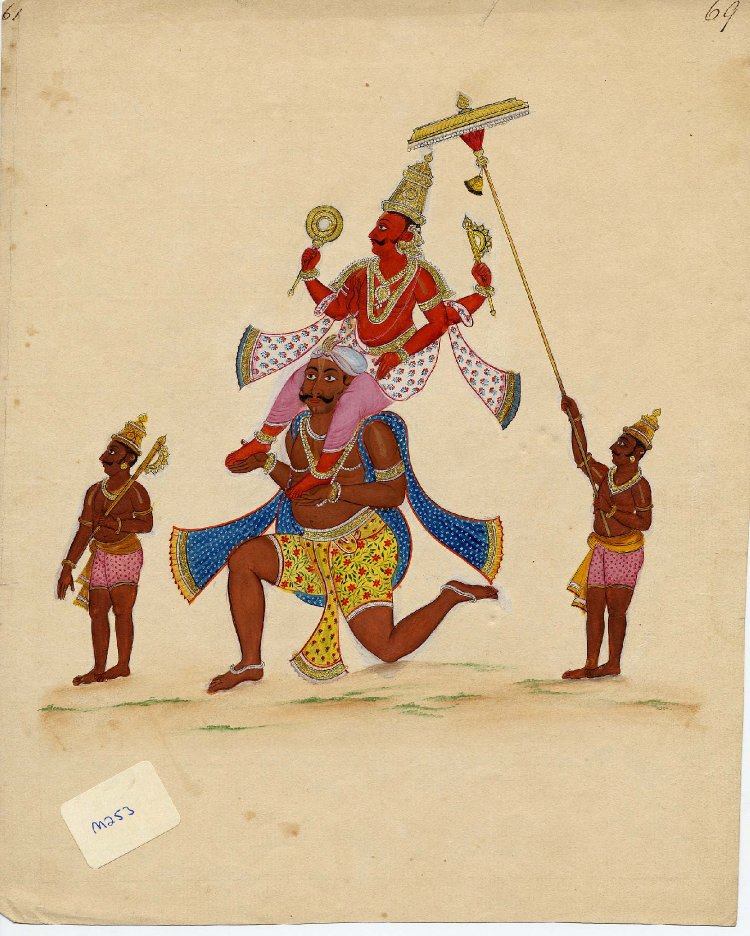

Niruti is the Guardian of the Southwest and commonly seen riding the Nara Vahana or Vedhala. Lance is his weapon.

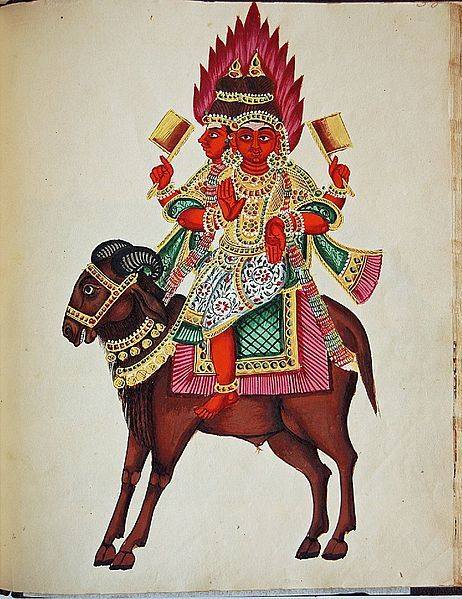

Agni, Guardian of the South east direction, rides the caparisoned Ram, seen mostly as two headed and seven armed, holding the Staff as his weapon, married to Svaha, and borne of Kashyapa Rishi and Aditi, and worshiped in all faiths.

Post and Photo Credits to Dr. Ravi Chandran KP